Updating the history of skateboarding: a book review by Eeva-Mari Haikala

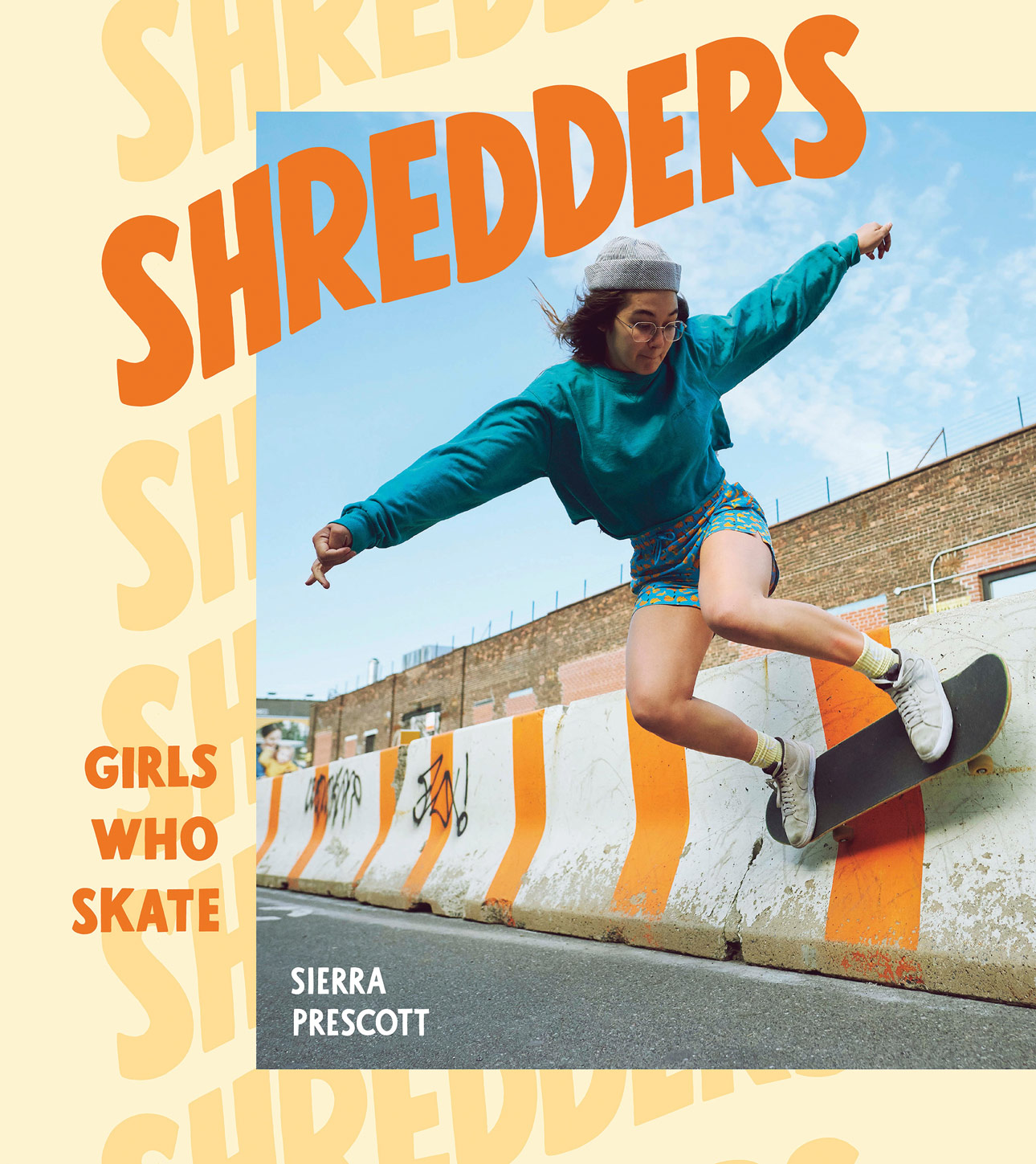

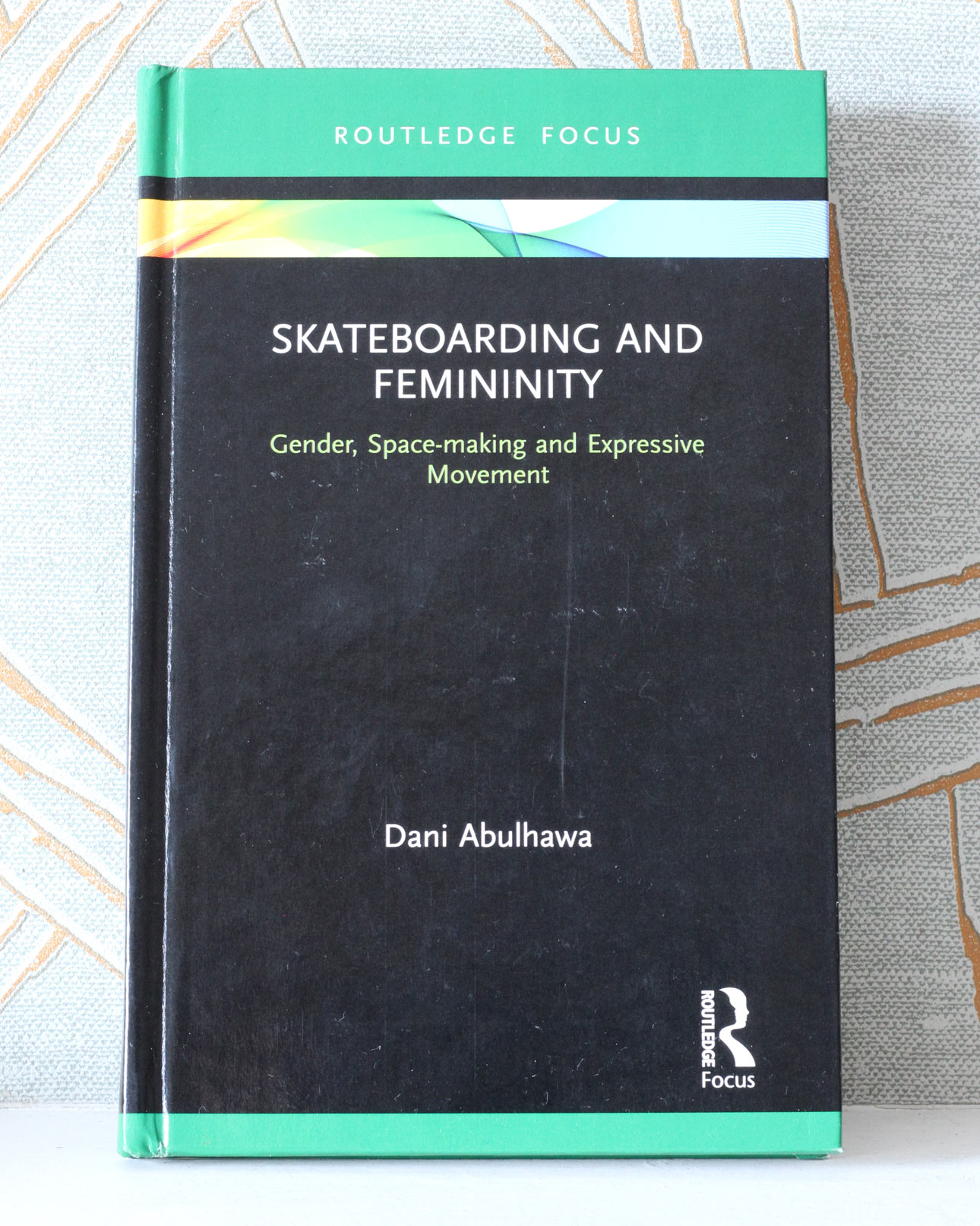

Some bright moments from the gloomy year of 2020 were a few good publications focused on female skateboarding. In this review I will write about two of them: Sierra Prescott’s Shredders (Ten Speed Press) and Dani Abulhawa’s Skateboarding and Femininity: Gender, Space-making and Expressive Movement (Routledge).

When it comes to skateboarding, women have always been there. When it comes to how the wider audience sees skateboarding, not so many women have been represented. Reasons for that are many; surely one of them is the skate media itself — the stories and histories of skateboarding which are told. Both publications observed in this article are brightening the chapter of ‘the role of female skateboarders’ to be more visible within the history of skating. These chapters have been written before, such as in Iain Borden’s comprehensive Skateboarding and the City: A Complete History (2019), which is a ‘bible of skateboarding history’. Nevertheless, it is important that there are publications giving full focus only to females, or to the gendered points of view in the culture of skateboarding. Writing history is always full of selections, and when the story is re-written or critically reviewed, it reveals why re-writing matters. Both Abulhawa and Prescott are giving historical and cultural explanations of what has made skateboarding so strongly considered an activity for (young) males, and how that image has started to change.

Prescott’s Shredders is gratifying on many levels. It is a book I wish I would have read when I was half-jokingly saying I’d like to try to skate, while at the same time belittling my wish by saying I am too old for that, and a female. Since those past days of mine, girls skating has grown to be more popular and visible (a phenomena Prescott’s and Abulhawa’s books deal with, and are part of); there are girl skateboarding associations, numerous womxn Instagram accounts and so on. Having said that, easy reading materials about the basics have been scarce. Prescott’s Shredders introduces both females on boards and the basics of skateboarding in a really clear way, which makes this book an excellent information source for anyone interested in taking first steps into skateboarding. Prescott describes, with the help of pictures, the anatomy of a skateboard and how to assemble one. Alongside, she explains names of different tricks and skateboarding slang.

“The film is well known amongst skaters (at least the older generation), but lesser known is the fact that Thrashin’ is loosely inspired by the all-girl skate and punk gang, The Hags.”

Skateboarding’s history is introduced, highlighting the main events from each decade, from the 1950’s till 2020. Prescott makes sure, if there was an active female skateboarder, it is mentioned. Another example of gendered history writing, also shortly acknowledged by Prescott, is an anecdote about the film Thrashin’ (1986). The film is well known amongst skaters (at least the older generation), but lesser known is the fact that Thrashin’ is loosely inspired by the all-girl skate and punk gang, The Hags. Prescott also gives explanations on why the role of girl skaters has varied during the decades. In the 1970’s when skateboarding was still a new activity, skateparks were a phenomenon accepted commonly by society. By the early 1980’s skating was in its decline, parks were closed, and the number of pro skaters diminished. Skateboarding moved onto the streets. The shift made skating accessible for everyone, which when looking at it from a gendered point of view, took many girls off the board. The disappearance of skateparks meant taking away a safe place to practice skating, especially when street skating was usually illegal, and the action took place at night times. All this has an impact on why skateboarding is still widely associated with young, risk-taking males.

When introducing the variety of skateboarding, Prescott divides skaters into three categories. All skateboarders are soul skaters for sure. Soul skaters in this book are those who skate for their own pleasure, for whom skateboarding is a lifestyle. OG’s are the pioneers of skateboarding, and pros are those who are sponsored and/or competing. With this division Prescott is able to give a voice for all kinds of skaters, not just to those who are most well known, or to those who land the gnarliest tricks. For me personally, alongside the action of skateboarding, the most appealing side of skateboarding is its ability to bring together all sorts of people. This is the attitude Prescott respects also. In her book she introduces, for example, a skateboarder who is a nurse and a mum getting on her board whenever she can in her free time. She is as legit a skateboarder as, let’s say, Lizzie Armanto, who’s also part of Shredders.

Prescott does not dismiss any type of board activity, as is often done within skateboarding. In Shredders, there is also long boarding, long distance pushing, and surfing. Even though the book is US centered, Prescott opens up the role of skateboarding worldwide using girl skaters as examples. One of these is young Ariel Cai from Shanghai. Skating in China is still widely seen as an anomaly, let alone if you are a girl. Cai is also into diving, which is a legitimated sport in China. Her dad allowed her to leave school a bit earlier to be able to practice diving — and this time is also used for regular skateboarding. At the same time, due to skateboarding being accepted into the Olympics, China has started to build huge skateparks — which Ariel Cai totally shreds.

In Skateboarding and Femininity: Gender, Space-making and Expressive Movement Dani Abulhawa goes deeper than Shredders into problematics of gendered history writing, taking along non-binary skaters. There’s no point to juxtapose these two publications, as their intentions differ. With their unique voices, Prescott’s entryway attitude and Abulhawa’s academic accuracy, fill the places there’s been within skateboarding culture. Abulhawa is an academic and a soul skater, if using Prescott’s definition. Abulhawa’s background settles the point of view for her book. It has four chapters: Introduction: Getting connected to who you are; Girls and women holding and creating space in skateboarding; Skateboarding and feminism; Skateboarding physical culture; and ‘Skateboard philanthropy’: A somatic perspective. Instead of giving a wide review of Abulhawa’s writing, I will focus on a few points argued in her book. For the rest, I strongly recommend everyone who is interested in skateboarding’s diverse culture to read this book. Not least, because there aren’t too many academic publications about skateboarding, yet.

“…critical awareness has had an impact on how the skate industry and culture have been both seen and represented by women. Examples are numerous, as are naked women on skateboard graphics.”

Abulhawa scrutinizes the problematics of gender within skateboarding culture and history, which naturally has a great impact on how skateboarding has been seen in a wider cultural context. She gives attention to how critical awareness has had an impact on how the skate industry and culture have been both seen and represented by women. Examples are numerous, as are naked women on skateboard graphics. The skate company Girl walks a tightrope with this, as Abulhawa observes giving the company’s history as an example of critical self-reflection within the culture of skateboarding. The name Girl refers to the widely objectified female body in skate culture. Meanwhile the visual logo is a dehumanized symbol of ‘girl’s toilet’. Abulhawa gives attention to the ‘gender blindness’, which definitely still occurs in the culture of skateboarding. Girls only skate sessions have been criticized to be dismissive, or they have been seen to matter only because (girl) beginners might not be confident because of their skating skills. Abulhawa draws attention for the importance of these sessions: the possible threshold (for girls and non-binaries) to enter skate spots derives from how skateboarding has been culturally represented as a male dominated industry. Abulhawa also highlights other contradictions within skate culture. For example, she gathers together the mixed reception Leticia Bufoni has received following her appearances on underwear or nude photographs published in Men’s Health Brazil and ESPN’s Body Issue. Others saw these taking away the attention from skill and ability, which is how male skaters are reviewed; others as an appreciation of the human body.

In the chapters Skateboarding physical culture and ‘Skateboard philanthropy’: A somatic perspective Abulhawa argues skateboarding shares the same values as somatic practice, which more commonly is associated with dance, self-knowledge and creative self-expression. When writing about the skateboarding charity projects, such as SkatePal, that builds skateparks and teaches skateboarding in Palestine, Abulhawa advocates for “giving the idea of skateboarding as a creative practice because it could contribute to improved innovative capability”. For me, this resonates with another thought expressed throughout Abulhawa’s writing. By scrutinizing (skateboarding) history and culture it gives an opportunity for change and development.

Skateboarding is its own culture. It has its own history. Meanwhile, it is part of the society and world we are living in. The history of skateboarding reflects what is happening in a wider cultural context, and vice versa. Thus, rewriting HIStory matters.

As skateboarders, we have embraced the idea of ‘skating and destroying’ and ‘skating and creating’. But increasingly, we also need…

Sahten paints a picture of the current skateboarding scene in Palestine, told in the form of a cookbook.

Pushing Boarders is the world’s only skateboarding conference, connecting a wide range of socially progressive groups and individuals, from emerging…